Edward Tang - Artistic Portfolio

Resume .................... Biography & Artistic Statement .................... Exhibition Experience

Global Communication Systems in Online Worlds

By their very nature, massively multiplayer online games lend well to group formation. Much has been discussed about the formation of gaming guilds and clans. These player groups are usually formed around certain common beliefs and/or motivations within their game of choice. A large amount of the actual group experience happens outside of the game using the World Wide Web and chat services to create and maintain the community. These player communities offer the potential for close friendships and other personal connections between the members. The bonds that are formed with spending time together performing a common activity as well as the spirit of teamwork can be just as strong in an online game as anywhere else offline.

Online games have come a long way technically since the early text based MUDs that have been captivating millions of players for over 20 years. However, one aspect that is still lacking from the new generation of Massively Multiplayer Online Games is the implementation of ingame global communication channels, i.e. chat rooms and a global message board system. There are no technical reasons why such a system can’t be implemented and the fact that users are forced to leave the game environment to use such tools weakens the possibilities for community and culture building to actually occur. Many reasons of why guilds exist are because of these shortcomings.

One game that effectively used global communication systems to build a dedicated player community is the Battletech 3030 MUX, where the Wizards have implemented several systems that could be incorporated effectively into a much larger game. Battletech (better known by its offshoot Mechwarrior) is a tactical board game from the 1980’s featuring a future universe under a constant state of war waged by giant robots called Battlemechs. The fictional world beyond the paper maps and cardboard playing pieces was supported by a wealth of sourcebooks and novels and reference books filled with technical readouts and game statistics of hundreds of these battlemechs. The result was a fleshed out and believable fictional world that provided the framework for many battles to be fought and stories to be told.

For many people familiar with the game, the main appeal was that setting, not the actual boardgame itself, which was unfavorably compared to taking a standardized test as players rolled dice and filled little bubbles on their information sheets to indicate damage to each others’ mechs. However, the computer games, first published by Infocom (incidentally, a game I still have in box somewhere in Seattle), brought the game to a more mainstream audience.

People continued to create alternatives to the board game. Based off of commonly available MUSE code, the first Battletech 3025 online game went online in 1991. Unlike other text based multi-user games of the time, it featured a combat system that began to accurately capture the complexity of the Battletech board game. The next year, the Battletech 3056 MUSE, which provided much of the foundation that even the current Battletech MUXes are built on. At its height, Battletech 3056 had up to 300 players online at once, both actively role-playing and fighting tactically in the game world against each other. There weren’t a lot of reasons to fight outside of character, but it provided a compelling enough experience to last until 1995 when it was forced to shut down due to loss of hosting.

Soon the MUXes settled down into two archetypes — one a simulator center model where players gained experience and money by participating in short fights in a gladiatorial arena with their battlemechs. The second type of MUX runs 6-8 week scenarios where players would organize into factions to fight in real time on a persistent map (called "Real Space" over resources and military supremacy. Players in that format are encouraged, in fact required, to come up with their own organizational systems within their factions.

All the time while this complex game runs, there is a strong social community within the MUX around multiple chat channels and bulletin boards accessible to everyone not currently in Real Space (more on this later). One major element of the community that ties everyone together is language:

"Bog, I fear your !clue, you boozed away all our good mex!"

(Translation: Geez, I’m afraid of your cluelessness, you lead that mission and your incompetent ass lost all of our good battlemechs!")

"Nog, I suxors."

(Translation: Yeah, I’m not very good.)

Over the years the culture of the Battletech MUX community developed their own language for use within the game. This vocabulary was derived from several different sources that the playerbase was involved with before they entered the game and through "oral" tradition and documentation it continues to this day.

The first source was the fictional Battletech universe to begin with, for example, words like "aff" for affirmative, "neg" for negative. While role-playing wasn’t necessarily enforced or encouraged, the use of in-universe vocabulary greatly added to the sense of being a part of that world. Abbreviations for the hundreds of ‘mechs and factions are also used freely as a convenience without explanation which can make a typical battle report incomprehensible to a new player.

Several computer science conventions have also been incorporated into the vernacular. The exclamation point ("!") used in the C programming language to denote the opposite or "not" of something ("!=" means not equal) is used freely in discussion (boy, that newbie is so !clue) and in game status reports ("!CS" means non combat-safe).

However, the most influential source of Battletech MU* was a MUD called Genocide. Genocide is a 24/7 player killing MUD (apparently one of the very first) that’s been running since 1992, and a dedicated community of players who started off together on Genocide has been running around the internet spreading their language and their gameplay skills:

Quote from xtc, longtime Battletech MUX player.

------

There were several players who came from Geno to the btech world. The most notable was soltan. He is considered the best person to ever play genocide by most. He came, as did wintermute and a few others. I came over with drizzt from genocide. We joined Waco Rangers in Dreamer's Battallion. I forget who Brian Dreamer was on Geno, but he was geno too. Anyway, the Geno folks actively recruited people from Geno, some of whom stuck around. Only one who I know that still plays btech is bc. He doesn't play here, and I haven't seen him in awhile, but he's Bishop on Geno, and played as Bishop Childers on 3029, and a few other muxes.

Some of the early geno players were among the best btechers. Notably again Soltan, aka Darkhosis, who seems to excel at anything PvP. Last time I saw him was when mpbt3025 came out. He and Ise from 3029 and a few others from geno/btech had a clan. Geno people generally moved on to other PvP endeavors.

As for the slang, it's catchy and tends to rub off wherever geno people go. Geno is still a pretty tight-nit group, and they make forrays into other games on occasion. With the advent of the MMORPG there have been Geno clusters in most of them. Notably, EQ, AC, DAoC, AO. They are more akin to PvP though, so we do genoclans in FPS, etc. Geno dominated AQ2 (Action Quake mod for Quake2) and more recently Global Operations.

------

Early Diku MUDs spread their own language and shorthand within their own games. Because most of those MUDders went through Genocide before coming to the MUX, such MUD language is referred to as "genospeak" on the Battletech MUXes. Three words in particular are tied to genospeak:

"Bog" : short for "Boggle," a common social on MUDs indicating confusion and surprise. For example: "Bog, that foo blew my mech up."

"Nog" : A butchering of the social "nod" which indicates affirmation or agreement. Or as the MUX helpbot indicates:

------

[Help] HelpBot: Well, Max Vision, Nog is "genotalk" for "sure thing, bubba."

------

Example: "Nog, that feg ganked you hard."

"laf" : Short for the social "laugh."

Example: "Laf"

Variations abound in the language on the games. Often "-le" suffixes are added to the words ("noggle"). Borrowing a page from hacker culture, words ending in "-"cks" or "-chs" are often ended with "x" instead ("Those mex sux."). As the playerbase is predominantly straight young male players are often referred to as "fegs" or "feglars."

Much of the vocabulary is propagated within the game via the online help chat channel, so any newbie can ask an automated bot what a particular word means. As new words enter the collective vocabulary of the players they are often added to the Helpbot. For example, one player known as Barry "booze" White was well known for leading well skilled players in expensive battlemechs on missions that through terrible play often lead to the mechs being destroyed and pilots all captured or killed. After booze declared his "retirement" from the game (he came back later under a different name), his reputation lead to his name being associated with awfulness in the game. A good player who stupidly lost a mech was deemed to have "boozed" his mech away, a lousy mission would be referred to as a "boozeop."

------

[Help] Max Vision: boozeop?

[Help] HelpBot: Well, Max Vision, Boozeop is an op named after Barry "Booze" White, the ringleader of Jerry's Kids... you know, take clued pilots out, driving ultra-prime mechs, then lose 'em all to complete stupidity and incompetence.

------

Online games offer the potential for stories to be told and reputations to be forged, and while the scenario based structure of the MUX implies that it isn’t necessarily as persistent as a game like Everquest, player lore is propagated both verbally and through the helpbot,, ensuring anyone with enough curiosity can learn about legendary players of the past. Often, a wizard will code silly tidbits about regular players into the helpbot:

------

[Help] Max Vision: jazz?

[Help] HelpBot: Well, Max Vision, Jazz is one of the goobers on this MUX. A veteran type. See also: yoohoo.

[Help] Max Vision: yoohoo?

[Help] HelpBot: Max, you may try asking about: Jazz.

------

….or more pointlessly…..

------

[Help] Max Vision: sin?

[Help] HelpBot: Well, Max Vision, Sin is genospeak for pimp.

[Help] Max Vision: pimp?

[Help] HelpBot: I've heard that Pimp is genospeak for Sin.

------

…. or more inanely……

------

[Help] Max Vision: ching?

[Help] HelpBot: My crystal ball says that Ching is one of the more insane players in this MUX, addicted to spice girls, dope, bright colours and pendosex.

[Help] Max Vision: spice girls?

[Help] HelpBot: Max, you may try asking about: Ching.

------

… and so on and so forth.

The availability of an easily accessible reference like that helpbot is important to the spread of slang and lore. To many players, a word isn’t legitimate until its been added to the Helpbot, much like how the dictionary is viewed as an official arbiter of new words in the English dictionary nowadays. At the moment the database for the HelpBot on the MUX is controlled strictly by the Wizards, but there’s no reason why it couldn't be opened up for the community to edit. One very interesting part of the HelpBot functionality is that it logs requests for definitions that don’t exist so that the Wizards can see what people are asking about and add content if needed.

Over the last few years the active playerbase on Battletech MUXes has shrunk noticeably. The availability of graphical games such as Everquest and Asheron’s Call affected MU* populations across the board. Instead of turning inwards in their efforts to preserve their community, the wizards provided the structure within the social functionality of the game for players who are off playing other games.

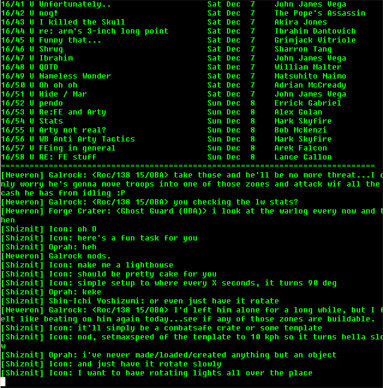

Like any online game, much of the discussion involves subject matter other than the game itself. The public chat channel is often used for discussing sports, the weather, computer matters, and other games. Often times, when a subject matter becomes particularly compelling, the wizards will add a specialized chat channel just for the subject, like baseball:

------

[Baseball] Tom Sawyer: Dodgers/Arizona is neck and neck

[Baseball] Nikki Jorgensson: <Go Dodgers...err...> isnt running outta pitchers much the same as running outta players?

[Baseball] Nikki Jorgensson: <Go Dodgers...err...> I mean, theoretically everyone on a roster could be used as pitcher.

------

Other subjects have included Romance languages or how Max Vision is a lousy player —

------

[MaxSux] Josep Sanchez: <Moo> fegalor

[MaxSux] Max Vision: <Sexy> bog

------

Most interestingly though are the channels dedicated to other online games. If enough player chatter goes on about a particular game a channel will be created for it to keep the noise on public channel at a decent level. The latest example of such a channel is channel "Neveron," dedicated to the online web based strategy game by the same name. If anything the MUX serves to enhance Neveron by bringing in an influx of interested players (the game itself was mentioned by the wizards in a announcements post) and providing a real time chat interface for a group of dedicated participants. On one hand it isn’t good for a MUX if their players aren’t actively playing their game, on the other hand its good to keep them logged on and around. After all, they might just get the bug again and start being more active in the MUX again.

-How MMORPGs don’t get this right:

The first problem with most MMORPGs is the lack of integrated communication systems within their game clients. If a user has to log out of the virtual world, quit the game client, then launch his web browser and get to the URL of the discussion board to talk about his favorite game, he’s definitely less likely to participate.

There are other problems with that separation of game space and social space.

Having to leave the game space makes for less immediacy in the communication and it becomes less likely that in character interaction will occur. The separated nature leads to a decentralized nature, which means that there are multiple message boards across the world wide web discussing the same topics relating to the online games. Information can be very hard to find.

There are issues though with an integrated communication system. One is the problem of cheating and sharing crucial game information that would break the immersiveness or fairness of the game. The MUX has an elegant solution — not allowing players access to the mail or message board capabilities while they’re in Real Space. In a sense Real Space is a sacred space where communication is limited to combat and mission related chatter with your own teammates over the radio.

Where is everyone?

MMORPGs can easily integrate the same or reverse approach to the Real Space idea. One way is to make that distinction between cities and wilderness in a game such as Everquest. If a player character is in a safe city, they have access to the boards and mail. If the PC is in an unsafe zone they’re not allowed. The concept can be taken further and an element of fantasy game city design can finally be taken advantage of — the city’s taverns and town halls. Right now most city buildings in Everquest are empty and dormant. Players have found more convenient and useful meeting areas in the cities. However, if a message board system were implemented as a town bulletin board in the corner of a tavern, players would have a real reason to gather and socialize in those purposefully built social areas. Random social encounters have a chance of happening! Possible (but at this point in server populations, not necessarily guaranteed) problems with scaling such a system could further advantage of in game geography and use continents or planets, for example, as delineators.

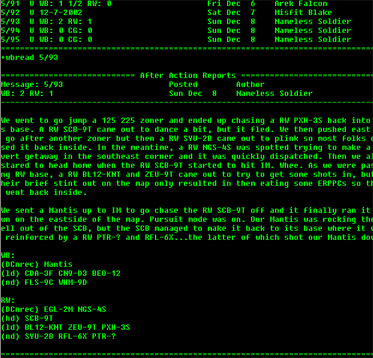

Attempts have been made to consolidate player created content into appropriate repositories, such as player lore and authored guides in online libraries. Things definitely need to continue in that direction. There’s no reason, for example, that the MUX helpbot couldn’t be player created, perhaps with a built in feedback system for good entries. How else would language and lore spread? A global forum in which a player could publish himself would certainly encourage players to write good stories about their experiences in the game. Right now that is happening within the guilds, but those stories and discussions are spread out all over the World Wide Web. Why aren't they consolidated? The skill of writing a good battle report (or AAR, After Action Report) on the MUX has become a fine art:

To many players on the 3030 MUX, the MUX is more than just a free game in which they telnet into everyday, it is a comfortable corner of the online gaming world that exists as a launching pad for new adventures across the internet. It’s a place where people will come back to, where people know each others names. There is so much potential for a graphically immersive world to share those wonderful traits and make more progress towards creating a real virtual world.

Links:

http://btech.ecst.csuchico.edu/~mux/ - The Battletech 3030 MUX website.

telnet: btech.ecst.csuchico.edu 3030 - The Battletech 3030 MUX (telnet)

http://home.pacifier.com/~dhawtho/battletech/ - Good (if incomplete) website about Battletech MUX.

http://www.iowa-mug.net/muddic/dic/ - An interesting MUD slang dictionary (lookup nog and bog!)

(special thanks to foc, xtc, tt, nique, mt, syxx, ka, aya, groz, v, pendo, and pewi from 3030 MUX)

e-mail me at edtang at antiexperience.com